Insights, Ideas and Project Highlights

If you missed the event in person, just click "learn more" below to go to a recording of the event. As always, if you want to find out more about working with Midion, click "contact" below.

Why Midion is the Right Partner For Your Next Project

By Jason Klous

Finding the right partner can make all the difference when embarking on a new project. At Midion, we have over 25 years of experience partnering with clients to deliver some of the industry's most challenging and innovative projects. But what sets us apart isn’t just our expertise—it’s our unique approach to project delivery. With a focus on developing people, building trust, and mobilizing new practices, Midion is the ideal partner to help you deliver your next project.

"Midion has a history of working successfully in this industry. Their background brings an authenticity and a way to connect to the people we’re working with.”

Matt Shipley, GM, AMTS

The Midion Method: Redefining the Problem

At Midion, we don’t just solve problems; we redefine them. Our approach to project delivery is not about finding quick fixes but redesigning how project commitments are coordinated in conversations to produce sustainable change in how work happens in your organization. We focus on what we call the central challenge of project work—a complex system of human coordination that exists in a background of historical practices that produce mistrust and bad moods. Traditional approaches focusing on tools and technology miss this critical element, but we embrace it as a core driver of success.

Through our project execution system, the Midion Method, we emphasize the importance of managing moods and creating a commitment-based approach to building high-performing teams that deliver exceptional results. We get those world-class project results when we combine our focus on the human experience with proven practices like lean construction tools and methods. When you work with Midion, we don’t just produce spot improvements; we create environments where innovative coordination and new communication practices redefine what’s possible and lead to permanent changes in how your teams work.

“With Midion's help, we cut through a lot of BS to get stuff done quickly.”

Ed Fitzgerald, Pharmaceutical Executive

Human Coordination at the Center

Midion sees human coordination as the key to unlocking better project outcomes in an industry known for inefficiency and complexity. The construction industry has historically been bogged down by poor communication, conflicting priorities, and wasted human potential. By addressing these issues head-on, we’ve transformed how teams operate.

Our approach involves developing new ways of listening, speaking, interpreting, and interacting with team members. Leaders are trained to address moods, emotions, language, concerns, and listening in daily project management. This emphasis on the human side of construction enables smoother coordination, faster schedules, and high-performing teams that work in unison toward a common goal. Why does this matter? Human coordination is the centerpiece of any successful project. You cannot rely on technology or tools to replace meaningful conversations that produce coordinated action. We see a 20% reduction in delivery time from the initial baseline schedule on our projects because of this enhanced coordination.

“With the fast-paced nature of our high-tech projects, continuous training and quick integration of new team members are crucial. Midion has been essential in maintaining our project's momentum and success.”

Katie Coulson EVP Skanska Buildings USA

Building Trust and Competence

Trust is foundational to any successful project. At Midion, we focus on building that trust through clear communication, collaboration, and accountability. Our process goes beyond managing tasks; we work closely with project leaders and teams to cultivate a culture of commitment and mutual respect. This ensures smoother operations and enhances the project's long-term success.

Moreover, we focus on developing the core competencies that your project needs to succeed. We engage teams in meaningful conversations, articulating shared ambitions and committing to building a successful future together. In this way, we build not just teams but communities of people fully invested in the project’s success.

A Learning-Centered Approach

Construction projects are unpredictable by nature, and adapting is crucial. Midion’s learning-centered approach encourages teams to embrace mistakes and continually evolve. We create an environment that fosters growth, enabling teams to learn from each project and refine their skills for future success.

This emphasis on learning is critical to our ability to innovate and deliver superior results. By focusing on adaptability and continuous improvement, we help projects stay on course even when unexpected challenges arise.

Fostering Moods of Ambition and Wonder

The mood of a project can significantly impact its outcome. At Midion, we recognize that moods are contagious and have the power to shape the attitudes and behaviours of everyone involved. That’s why we aim to foster moods of ambition and wonder in every project we partner on.

By creating an environment where people feel inspired and explore new possibilities, we spark a sense of wonder that encourages innovation and creativity. These moods propel teams to think beyond the ordinary, push boundaries, and strive for excellence. Instead of resignation or mistrust, we cultivate a culture of ambition and wonder, where team members are not just doing the work but are motivated by what they are building together.

This cultural shift, combined with our innovative coordination methods, leads to faster, more efficient project completion and leaves everyone involved with a sense of pride and accomplishment.

The Midion Promise

Our track record speaks for itself: Midion has been a trusted partner on some of the industry's most complex and innovative projects. But beyond our experience, our unwavering commitment to creating better futures for our clients makes us the right partner. We promise to bring not only the skills and expertise but also the trust, language, and learning environment needed to ensure your project’s success.

"Midion played a pivotal role in transforming our data center project by focusing on what truly matters—team building and people. With their strategic guidance and partnership, we were able to foster stronger collaboration, enhance communication, and align everyone on the same goals. Their emphasis on trust and accountability among all stakeholders allowed us to tackle challenges head-on in the right way."

Brad Barton, EVP at Applied Digital

Partnering with Midion means choosing an experienced, innovative, and human-focused approach to project delivery. We are your trusted partner in building the future. Let’s build it together.

LeanProject is Now Midion: Mobilizing Teams and Building Results

.png)

Saint Paul, MN, October 14th, 2024 — LeanProject, a leader in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industries, has rebranded as Midion. This new name represents the company’s expanded focus on creating world-class teams, fostering collaboration, and delivering impactful results in complex project environments.

Founded in 1999, LeanProject has been a trailblazer in introducing innovative practices like the Last Planner™ System and Integrated Project Delivery. The rebrand to Midion reflects the company’s evolution from its lean construction roots to a broader, more holistic approach that integrates a commitment-based management approach with Language Action, trust, moods, and lean construction to create successful projects.

“Our rebrand to Midion underscores our growth and transformation over the last 25 years,” said Jason Klous, Principal at Midion. “We’ve moved beyond our original focus on lean tools to becoming a trusted partner that helps clients build successful teams that can achieve real success in the built environment.”

Midion, derived from an ancient language meaning togetherness in action, reflects the company’s core belief in collaboration. While the name and visual identity are new, the company’s mission remains the same: to drive positive project outcomes by building strong, world-class teams that can navigate the complex project environment.

For existing clients, this rebrand signals Midion’s continued commitment to helping them complete projects on time, on budget, and achieve the project's business goals. By emphasizing people-centered processes and effective collaboration, Midion ensures that every project benefits from seamless teamwork and expert strategy.

“Midion’s approach has been a game-changer for us,” said Katie Coulson, Senior Vice President of Skanska USA and a longstanding partner of the company. “Their ability to align our teams and keep complex projects on track has consistently delivered outstanding results.”

Alongside the name change, Midion has updated its visual identity to better reflect its modern approach and innovative methods. The new logo and branding elements symbolize precision, collaboration, and forward-thinking solutions in the built environment.

Looking forward, Midion is committed to staying at the forefront of industry innovation and continuously refining its approach to project delivery. “Our focus is on helping our clients adapt to the evolving demands of the construction industry,” added Klaus Lemke, Managing Principal at Midion. “We empower organizations by instilling the structure, practices, and skills to ensure effective teamwork and successful outcomes on every project.”

About Midion

Midion mobilizes practices through people and structures in the built environment, focusing on collaboration, care, and a shared commitment to success. With over 25 years of experience, Midion partners with clients to form world-class teams that deliver measurable results and effective project outcomes. Guided by a holistic approach, Midion builds authentic relationships and innovative strategies to help organizations navigate complex challenges, achieve lasting impact, and drive meaningful results in the architecture, engineering, and construction industries.

Learn how Midion can help you complete your projects on time, mobilize high-performing teams, and deliver impactful results at www.midion.com.

Media Contact:

Colleen Kranz

Chief Marketing Officer

612.440.5326

info@midion.com

Towards a Zero Punch List Project

Project defects are so common that most construction companies have a procedure to deal with them. Can we make defects obsolete?

Traditionally, we have accepted defects on construction projects as a fact of life. Perhaps defects continue to occur because both managers and workers treat them more as an annoyance than an opportunity for learning.

In this paper, we look at the usual approach to defects and present some alternatives that are easy to implement. We show that using defects as the core of a systematic learning process can lead to their permanent elimination.

Project Delivery Partner: How to Deliver Exceptional Outcomes

Poor communication can cause project failure. Break down silos and reduce project timelines by 30%.

Introduction

The construction industry is no stranger to complexity.

Cost overruns, project delays, miscommunication, and a lack of true collaboration can - and do - cause projects to fail. That’s why simply managing a project isn't enough; leaders need to harness all the team's potential to achieve the execution goals. Solving this challenge is where the strategic guidance of a Project Delivery Partner becomes essential.

A skilled partner brings expertise, leadership, and a structured system of communications that elevates the Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) methodology in a way that transforms projects and drives exceptional results.

What is Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)?

Imagine a complex, time-sensitive, mission-critical construction project. Now imagine that all of the people and processes are working together in harmony and delivering the project on time and on budget. That’s the goal of IPD.

IPD offers a refreshing approach to construction. It’s all about collaboration. The goal? To achieve outstanding project outcomes.

To achieve the project’s goals, the team will strategically and systematically elevate the collective talents of everyone involved. The result is measurably improved outcomes, producing flow, effective coordination conversations, and more effective communication.

How does IPD drive these lofty outcomes? It all starts with shared risk and reward, early stakeholder involvement, and these five big ideas for reshaping project delivery. These principles laid the foundation for the new way to deliver construction projects. The ideas have reshaped construction by embracing teamwork, learning, and accountability.

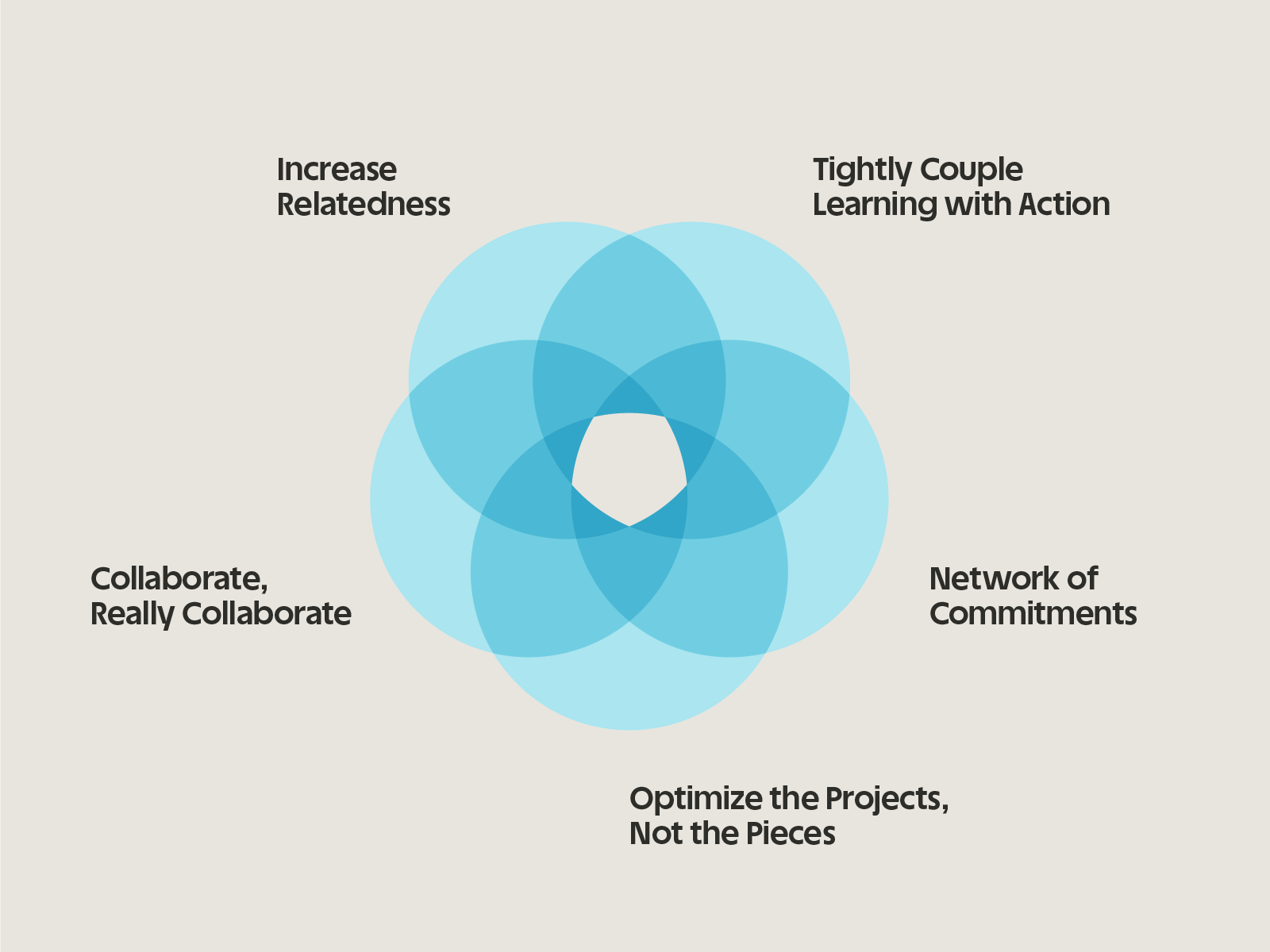

The Five Big Ideas reshaping the design and delivery of capital projects:

- Collaborate, really collaborate: Align interests for shared goals.

- Optimize the whole project: Avoid local optimization that hinders overall success.

- Tightly couple learning with action: Integrate continuous improvement through metrics and reflection.

- Projects as networks of commitments: Ensure reliability in project commitments.

- Increase relatedness: Build trust and relationships for better teamwork.

These principles set IPD apart. Traditional methods, like design-bid-build, often suffer from limited collaboration. Information silos can hinder progress. IPD breaks down those barriers through mutual respect and trust, a willingness to collaborate, and open communication.

It’s important to note that IPD spans all project phases, from design and fabrication to construction. To learn more, download a free copy of the University of Minnesota’s white paper on integrated project delivery here.

Project Delivery Partner vs. Integrated Project Delivery: Clarifying the Roles

What is the difference between a Project Delivery Partner and Integrated Project Delivery? Do I need both?

Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) is a methodology—a framework for executing a project.

A Project Delivery Partner is a partnership—the expertise and guidance provided by a specialized team to implement IPD and deliver your project effectively.

While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, it’s crucial to understand the distinction between a Project Delivery Partner and Integrated Project Delivery.

Think of it this way: IPD is the what, and the Project Delivery Partner is the who and the how.

A skilled partner brings the experience, leadership, and facilitation skills necessary to unlock the full potential of IPD. They act as a conductor, orchestrating the various stakeholders and ensuring everyone is working towards a shared goal.

Ready to explore how a Project Delivery Partner can transform your next project?

Why Choose Integrated Project Delivery with a Project Delivery Partner?

Combining IPD with a dedicated Project Delivery Partner amplifies the benefits exponentially. A partner brings:

- Enhanced Collaboration: Facilitate communication, break down silos, and foster a truly integrated team.

- Proactive Risk Management: Identify problems early and mitigate potential risks.

- Measurable Cost Savings: Maximize resource utilization through Target Value Delivery and efficient processes.

- Improved Project Outcomes: Focus time and resources on quality and innovation for better results and higher client satisfaction.

- Specialized Expertise: Receive access to expert coaches with proven methodologies and lessons learned from other successful projects – fully customized to your project’s needs.

According to research from the Lean Construction Institute, IPD projects are significantly more likely to be completed on time and within budget compared to traditional projects.

How It Works: Integrated Project Delivery and a Project Delivery Partner

A Project Delivery Partner plays a crucial role throughout the entire IPD process, from project inception to closeout. Their involvement typically includes:

- Project Definition: Helping define project goals, scope, and success criteria.

- Team Formation: Facilitating the selection and onboarding of key stakeholders.

- Collaborative Design: Leading workshops and fostering the Target Value Delivery Process.

- Risk Management: Developing and implementing risk mitigation strategies.

- Construction Execution: Tracking construction activities and ensuring alignment with the project plan.

- Project Closeout: Conducting post-project reviews and capturing lessons learned.

When and What to Look for in a Project Delivery Partner:

When should you consider bringing in a Project Delivery Partner?

Ideally, as early as possible. Proactive planning is best. Especially if you need to deliver an “impossible” project.

Often, however, a Project Delivery Partner is brought in when a project goes sideways or is at risk of failing.

That’s why choosing the right Project Delivery Partner is critical. Look for a firm that prioritizes:

- People and Culture: A partner who understands the importance of team dynamics and fosters a collaborative culture.

- Proven Outcomes: A track record of successful IPD projects and demonstrable results.

- Innovative Methodologies: Experience with cutting-edge tools and techniques, such as LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® for enhanced team collaboration.

- Strong Communication: Excellent communication and interpersonal skills are essential for facilitating collaboration.

- Deep Industry Knowledge: A thorough understanding of the construction industry and best practices.

Project Delivery Methods Compared

Several project delivery methods exist, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

IPD, when implemented with a skilled partner, often outperforms traditional methods like design-bid-build, design-build, and Construction Management at Risk (CMAR) in terms of collaboration, efficiency, and project outcomes.

A Project Delivery Partner can help you select the most appropriate method for your specific project needs.

Thinking About Hiring a Project Delivery Partner? Here’s What You Need to Know.

If your project faces challenges like communication breakdowns, cost overruns, or a lack of innovation, a Project Delivery Partner can be the solution.

Your Project Delivery Partner brings a fresh, outside perspective, plus the expertise and leadership needed to navigate complex projects and achieve strategic goals. Midion's consulting services, including construction project management consultancy and construction leadership consulting, address these challenges head-on.

Download our Integrated Project Delivery White Paper:

Building High-Performing Construction Teams: The Midion Method

Great construction methods and project management practices only go so far. The reality is that people, not robots, execute these methods and practices—and people are complicated.

The good news is that data tells us that when industry experts are collaborative project delivery partners who care for people, navigate challenges together, and focus on holistic outcomes, construction projects can be completed 30% faster, and billions of dollars can be saved.

What are the Midion Method principles?

Over the last 25 years, the Midion team has executed some of the most challenging projects and engaged in the most significant innovation conversations in construction and design.

From these experiences, Midion became the Project Delivery Partner who delivers measurably better outcomes.

The Midion Method Principles:

- Human coordination within construction projects is deeply social, cultural, and communal, with moods playing a critical role in influencing outcomes.

- Moods and norms reflect the historical and cultural background of the individuals and organizations involved, impacting how people think, speak, and act.

- The challenge in project delivery is not simply a technical problem for which there is a solution, but a complex situation involving human coordination and cultural change.

- Transforming project execution requires new skills that affect moods, language, and coordination, leading to more competent teams, faster schedules, and successful projects.

- A focus on learning, making mistakes, trust, and innovation is essential for building a better future in project execution, ensuring predictable operations and project success.

How the Midion Method works:

- Redefine the problem as a multi-faced challenge that cannot be fixed with a single solution.

- Interact with the key topics that leaders must work with every day—moods, emotions, language, concerns, and listening.

- Execute projects with new skills and coordination practices—plus new ways of listening, speaking, learning, interpreting, and delivering.

- Build faster, more successful projects and high-performing teams.

The Midion Method goes beyond traditional methodologies, focusing on building high-performing construction teams through construction project team building, construction project culture development, and construction leadership training.

Innovative tools like LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® foster team cohesion, enhance communication and unlock the collective intelligence of your project team.

Conclusion

For construction projects that are large, complex, and/or mission critical, a Project Delivery Partner is more than just an advisor—they’re a strategic ally. By leveraging the power of IPD and bringing specialized expertise, they empower projects to achieve exceptional outcomes.

Schedule a consultation with Midion today to discuss your project needs.

Klaus Lemke, Managing Principal at Midion, shares his journey to helping organizations and leaders get unstuck by asking different questions and showing them a better way. So many of us use the same thinking to solve our problems instead of challenging ourselves to think differently and have fearless experimentation.

Welcome to the Midion Minute, the monthly newsletter focused on improving results in the AEC industry.

Why Midion?

Our approach to project delivery is not about finding quick fixes but redesigning how project commitments are coordinated in conversations to produce sustainable change in how work happens in your organization.

Embracing a New Common Sense for Project Work

Could a shift in ‘common sense’ unlock unprecedented success for AEC projects? Here's what's possible.

Completing an Impossible Airport Expansion

The Port of Portland needed to expand, but this $2BN project would be a challenge for many reasons.

Client Profile: Derek Hoeschen – Project Executive, McGough Construction

Derek Hoeschen, Project Executive with McGough Construction, has left a lasting impression within the construction industry.

From Our Library: Academic Paper

Do projects have horsemen? An investigation of the warning signs of unreliable commitments.

Ready to transform your project outcomes?

At Midion, we’re dedicated to achieving your goals with faster schedules, stronger teams, and more successful projects. Discover how our coordinated action can lead to a better project experience and a brighter future.

Embracing a New Common Sense for Project Work

Few leaders in the AEC industry will claim that a majority of their projects could be categorized as “successful.” Sure, as an industry, we accomplish great things all the time. Our industry is responsible for designing and building the facilities that move the world forward, from state-of-the-art pharmaceutical plants, microchip factories, and AI datacenters, to manufacturing plants, infrastructure, housing and energy production to serve the needs of the next generation. Builders, designers, managers, and leaders are doing good work and accomplishing great things every day.

Room for Improvement

But how much better are we as an industry, really, than we were 20 or 30 years ago? Have we eliminated the health risks, stress, and fatigue of this work? Have we slashed the project delays, cost overruns, and contentious culture that plagues so many projects? Have we created an environment that invites new participants to join us in search of rewarding work and fulfilling careers?

Statistics show that while many industries, from farming to manufacturing, have made dramatic improvements, the AEC industry is surprisingly stuck in the past. We continue to rely on dated command-and-control management structures, prescriptive and restrictive procurement and contracting methods, and a general mindset based on mistrust, skepticism and defensiveness.

As an industry, we’ve known for a long time that we could do better, and there are signs of hope for a better tomorrow. While IPD and lean construction practices, when robustly applied, are creating positive results, the cure to our stagnation lies not merely in new practices, but more fundamentally in adopting a new common sense. I’m always puzzled when I hear someone from the industry declare that the solution is just “common sense.” Afterall, our current common sense tells us we can manage work through contracts, control risk by passing it to the party with the least control and influence, and improve outcomes by holding onto secret contingencies, protecting ourselves from others and building up our defenses. If we want to make real change, we need to adopt a new common sense!

A New Common Sense

The good news is that a proven model for this new thinking already exists, and in fact, has been around for decades. In 2004, Greg Howell, Hal Macomber and others wrote about this philosophical transformation in their IGLC paper, Leadership and Management: Time for a Shift from Fayol to Flores.

In his article, Greg is asking us to “reconsider the nature of work in projects,” to recognize that made. However, people are not the problematic units that, as Henry Ford theorized, need to be planned, organized, commanded, coordinated and controlled. Instead, people are autonomous, historical beings, who are capable of achieving amazing things in concert with others. So what’s the key to leveraging the incredible power of people, and more specifically, teams of people working on projects?

The shift that Greg spells out is based on Fernando Flores’ concept of making and keeping reliable commitments. This language may be familiar to many of you familiar with lean construction practices, however, we’ve seen this concept misapplied in practice more often than not. The problem is that when this concept is applied through the common sense lens of command-and-control leadership, it becomes a tool for coercing compliance, assigning responsibility, and keeping people on track - not so much different from Henry Ford’s top-down approach to management.

Focus on Trust

This outdated thinking misses the primary shift that Flores and Howell were advocating. The practices that lead to clear requests and reliable commitments are not primarily implemented as a way to ensure compliance with a schedule or achieve a specific task. Instead, the primary purpose is simply this: to build trust.

Trust is the key element ignored by contracts, schedules, operating procedures and plans.

Without trust, these are tools that live between parties, used for each individual’s purpose, and typically divide rather than unite us as a team. We’ve all seen what happens when there is little trust among team members, and most of us have seen what’s possible with high trust. While most leaders accept that teams with high degrees of trust perform dramatically better, there is little understanding of how to create this elusive trust in a practical, reliable way. Many think it’s a matter of luck, or chemistry, or maybe team building over bowling and beer. This may sometimes be the case, but that does not provide a reliable, proven approach needed for a new leadership paradigm in project work. This is where Flores comes in!

Our experience on projects of every size, in every industry, and utilizing every type of delivery method around the world shows that building and maintaining trust is not only possible, but it can be done predictably and quickly on every project. We’ve seen it over and over again, and have systematized the approach as part of the Midion Method. It’s the new common sense that leads to high-performing teams and unprecedented outcomes on every project!

Reliable Commitments

The key is to apply the concept of making and keeping reliable commitments at all levels of the project, and build the idea into every projects’ Structure, Practices, and Skillset. The approach is simple, and you can see a team begin to shift even as they make and keep the smallest commitments - showing up for meetings on time, providing information when promised, and admitting mistakes. These small moves build trust, and lead to more significant commitments - sharing real budgets and costs, working collaboratively in the best interest of the team, and exposing scope gaps and schedule busts while there’s still time to do something about them.

Building a powerful team around this system is not hard once you shift your common sense, and quickly transforming a struggling project becomes a real possibility. To see the power of this new paradigm for yourself, try it on for a couple days. On your current project, look at the challenges and bottlenecks through the lens of trust. What would happen to those biggest roadblocks if your team had more trust in each other - or even just in you? How would your team be planning for the future, anticipating problems, and raising expectations for their own performance if there was more trust? It’s easy to imagine how a project could be transformed if you could even move the trust needle just a little bit.

Now, think about one small commitment you yourself can make to start building more trust. Start by making an offer to one of your internal customers on the team, someone who needs you to perform. Make your commitment specific and clear. Check back to validate that you’ve kept your commitment and that it’s served the needs of your customer. In this simple step, you’ve started something that could change the future for your entire project team.

Client Profile: Derek Hoeschen – Project Executive, McGough Construction

We’re excited to spotlight Derek Hoeschen, Project Executive with McGough Construction, whose expertise and collaborative spirit have left a lasting impression within the construction industry.

A Career Built on Collaboration and Mentorship

Derek has spent his career working with world-class general contractors on high-profile projects across the U.S. His journey has allowed him to collaborate with top-tier design teams and owners while shaping and mentoring his teams. While initially challenging, his openness to relocation opportunities has become a source of personal and professional growth.

Reflecting on his experiences, Derek notes: “I wouldn’t trade those moves for anything—they’ve shaped who I am today.”

Midion and Derek: A Natural Partnership

Derek’s first interaction with Midion was through a six-month professional coaching session five years ago. That experience planted a seed, and when faced with a new, complex project in a remote location, Derek knew that his team needed Midion’s consulting expertise.

“The small-group coaching was a stepping stone into leadership and self-reflection. It’s taught me lessons I’ll carry forward for the rest of my life,” Derek shares.

Challenges and Values that Shape Success

Derek is candid about the challenges of construction delivery, especially in aligning budgets and schedules early in the process. “Problems are like garbage—they only get stinkier with time,” he recalls, quoting a mentor. Transparency and teamwork are his guiding principles, ensuring potential issues are addressed head-on.

His work is also deeply rooted in values such as trust, integrity, transparency, and hard work. These principles drive his leadership style and align perfectly with Midion’s approach: “Effective, yet not complicated.”

Looking Toward the Future

Derek is optimistic about the industry's evolution, especially the growing respect and technological advancements for tradespeople in the built environment. However, he remains mindful of the challenges ahead: “The desire for instant gratification can short-circuit important processes.”

As a forward-thinker, Derek sees artificial intelligence as a tool to simplify tasks and improve project delivery in the near future.

Passion Beyond Construction

Outside of work, Derek finds joy in aviation. Whether building, maintaining, or flying airplanes—or just watching the latest aviation content on YouTube—his passion for precision and craftsmanship extends beyond construction.

His motto, “Building success through collaboration, precision, and respect,” perfectly reflects his professional philosophy: fostering positive relationships, focusing on detail, and empowering all team members to contribute meaningfully.

Derek Hoeschen embodies the spirit of continuous learning and collaboration, and we are proud to feature his story. His partnership with Midion is a testament to the power of effective conversations, mutual trust, and shared success. We look forward to seeing what the future holds as we continue to build together.

Integrated Project Delivery: Case Studies

This document incorporates case studies originally documented in the 2010 publication, “Integrated Project Delivery: Case Studies” by the AIA / AIA California Council.

This study is a revision of our report published in February 2011. It advances the previous study with the inclusion of one new case study (University of California San Francisco, UCSF), report of the survey results and addition of the six cases documented in the 2010 AIA/AIA-CC publication of “Integrated Project Delivery: Case Studies.” Whereas previous case study efforts were limited to the handful of projects executing IPD, this effort is framed broadly, choosing projects of various program types, sizes, team composition and locations. Additionally, this set of case examples documents a wide range of team experience, from teams with quite a bit of IPD experience to those who are using their project as a learning experience. The level of experience of the teams is shown graphically in the at-a-glance pages of the matrix. Unique to this study is the opportunity to study projects from early phases through completion. Following projects over time, we hope to gain insight on the evolution of each project, its collaborative culture and areas of success and challenge. This document is focused on project activities that lay the foundation for collaborative practices in IPD.

An Overview, Analysis, and Facilitation Tips for Simulations that Support and Simulate Pull Planning

Pull Planning is an essential component of the Last Planner® System (LPS). It helps define how work will be handed off from one project performer (e.g., owners, designers, contractors, and suppliers) to the next. It illustrates how work is balanced between project performers to better support a project takt time, i.e., work completion rhythm. It encourages project performers to have conversations earlier about how to handle physical interfaces between components that may at first seem plausible in design but end up being much more challenging to accomplish in construction. Due to the importance of Pull Planning and the fact that it is a typical first step for lean implementation on Architecture-Engineering-Construction (AEC) projects, project teams that have limited Lean Construction experience can use a variety of simulations to ensure better participation during actual Pull Planning efforts.

Thus, to help accelerate the rate of Pull Planning learning and successful implementation in the AEC industry, this paper will provide an overview of simulations that have proven to be effective in supporting and simulating Pull Planning. It will discuss how they prepare project teams for actual Pull Planning efforts and provide insight into facilitation techniques based on the authors’ experience. It will address differences in teaching Pull Planning within an academic versus industry setting. In closing, we will provide a guide as to which simulations to prioritize when faced with limited time for educating students or training project teams.

Developing Production Theory: What Issues Need to Be Taken into Consideration?

The aim of this paper is to establish key issues that a theory of production should address, to conceptualize these issues and to sketch an account of their interaction. Aristotle's analyses of knowledge and causality are used, in conjunction with Wittgenstein's concept of language games, to integrate the insights of transformation-flow-value (TFV) theory and the language action perspective (LAP) within a framework derived from Liker (2004). Building on Liker, we identify four language games that are necessary for production:

- drawing on scientific knowledge to determine the best physical arrangements for the achievement of a pre-given value;

- two value discourses which determine

(a) the target value for (1) and

(b) the human relations which will enable the achievement of (1) - Liker's ‘long term philosophy’ and ‘developing people and organization’, plus the Language Action Perspective; - a discourse of learning and knowledge with the aim of continual improvement.

Four of the key concepts used in these games are identified (flow, work, knowledge and commitment) and related to the functions of management. Finally, an overall theoretical framework is proposed.

Workers at the Edge: Hazard Recognition and Action

Supervisors and workers report they work in the danger zone where errors can have terrible consequences. Current best practice safety programs aim to train and motivate workers to avoid hazards. These programs attempt to counter pressure for improved efficiency and reduced effort but are only partly successful. A new approach has been proposed that aims to improve safety by increasing the ability of workers to work safely closer to the edge where control is lost and accidents occur (Howell, et al, 2002). In this paper we review and propose the implementation of an approach drawn from aviation. Airline safety has been improved by a system designed to alert pilots of hazards identified by anyone on the flight deck. Crew Resource Management (CRM) protocols establish a safe and emphatic way to alert the pilot that the safety of the flight is at risk. This system is designed to overcome the reluctance of junior members to make suggestions to more senior officers. Specific simple communication rules are established to assure the gravity and source of the concern is made apparent without disrupting normal roles and responsibilities. While flying a plane is different from working in a construction crew, we suspect that construction workers are reluctant, for a variety of reason to speak up when hazards are encountered. Taking risks is considered part of the job.

This paper describes CRM, and proposes an experimental application in construction.

Development of Simulations & Pull Planning for Lean Construction

To manage projects based on Lean principles including global optimization, transparency, reliability, and flow, Lean learners need to learn an alternative approach that includes different language and techniques that better support production system management. By helping us model what happens in the real world while focusing on a few key concepts, simulations help Lean learners focus on how they would diagnose problems and determine how to deliver the project better. While Lean learners may think they are learning something during simulations, instructors are really getting them to reflect on how things happen and why. In essence, simulations help with “learning to see” waste and other problems on projects (Rother and Shook 1999) so Lean learners can develop strategies for waste removal and problem solving to generate value better.

How did the Lean Construction community adopt this training approach for Lean learners? This paper explores the Lean Construction community’s use of simulations (particularly the Airplane Game and Parade of Trades®) and creation of the Pull Planning technique. This reflection provides a foundation for instructors to share training practices and collaboratively refine their teaching approaches to accelerate the rate of Lean learning and implementation.

Resilience Engineering: A New Paradigm for Safety in Lean Construction Systems

Achieving reliable workflow between construction operations is paramount to the success of Lean Construction implementations. In Lean Construction, as in lean production, workflow of operations is affected by waste (muda), variability (mura), and overburden to workers and machines (muri). It follows then that reliable workflow in construction operations cannot be achieved without safe work practices, which is the concern of this paper. The work of Jens Rasmussen was used previously as a foundation to propose a new cause and effect model for the way construction accidents originate and propagate to injury. The model provided a conceptual framework to help workers better detect where hazards may be released, better cope near the boundary beyond which work is no longer safe, recover if control is lost, and finally to minimize the effects if loss of control is irreversible.

This paper presents a paradigm that investigates the ability of actors within an organization to anticipate and adapt before and after risk situations give rise to loss of control. The paradigm is dubbed “Resilience Engineering” in an attempt to signify that the ability to respond and adapt to unexpected changes can be engineered into organizational settings similar to how certain materials are engineered to be resilient — to recover to their original shape after being stressed. According to the pioneers of this field, a resilient organization is one that has mastered the art of managing and coping with unexpected events and following disruptive consequences. An underlying principle in Resilience Engineering is that understanding failure in order to prevent its reoccurrence is more profound when we understand how safety is created by people in workplaces with continually changing hazard sources and inevitable compromises between safe and productive actions. In this paper, the origins of Resilience Engineering are reviewed, focusing on what it is and what it isn’t. The paper concludes with propositions for implementing Resilience Engineering in construction settings and offers pointers to future research.

Better Building: Lean Practice for the Project-Driven Organization

By Klaus Lemke, Managing Principal at Midion

The business of creating our built environment remains largely siloed and disconnected today. Owners, designers, construction managers, and trade contractors each defend their profit margins by shifting risk to others and focusing on their own piece of the puzzle. Lean thinking promises to change all this, yet has proven particularly difficult to implement in the building industry.

Many great lean books provide insights and inspiration into a better way to operate, yet until now, none focus on the unique challenges of the design and construction industry. Better Building provides a practical model for putting lean thinking into action and improving the experience of project work.

Based on years of experience shifting mindsets and behaviors, this model answers the most often asked questions and provides a road map for navigating the toughest parts of a lean transformation journey in the project-driven environment.

Causes of Time Buffer in Construction Project Task Durations

Due to the inherent nature of the construction industry, all construction projects have some amount and type of uncertainty. Personnel involved with the project compensate for the uncertainty by adding buffers. This research is focused on “time buffers” added to construction task durations. We define “time buffer” as time added to task durations to compensate for uncertainty and protect against variation. Although previous research acknowledges this addition of time buffer, the root causes of buffer have not been thoroughly researched. The research objectives include determining which factors are the most prevalent and severe causes of buffer and determining opinion differences amongst various groups.

A survey was developed and then completed by 180 construction personnel across the United States. The top twelve most frequent and severe causes of buffer in task durations were identified. The factors were analysed in how they are viewed differently by foremen, superintendents, and project managers; trade to trade; general contractors to subcontractors; level of experience; and companies regularly using the Last Planner System® and those who do not.

The findings will help construction managers understand what drives the need for buffer in construction schedules and focus efforts on strategically addressing critical areas of concern or uncertainty.

Lean Safety: Using Leading Indicators of Safety Incidents to Improve Construction Safety

Safety and organization of a construction site were improved with the application of safety leading indicators and a 5-S assessment tool on a project managed using Lean principles. Safety related data collected on safety walks on a daily basis was organized for each specialty contractor and normalized for worker hours. The implementation of the 5-S assessment rated the site organization from zero to five for each contractor by a variety of key stakeholders. The observation of safety leading indicators provided a measure of safety risk on the construction site and a measure and mechanism for continuous learning. As a result, safety continually over the life of the project. Early results of the 5-S program clustered at the low end of the scale at the beginning of the project and significantly improved over time and reached almost 5 as the project approached completion.

The paper will reflect on related conceptual foundations and propose follow up investigations aimed at exploring leading indicators and other assessment tools related to safety and quality of work. The paper will also explore challenges faced by a general contractor in the on going efforts to implement the leading indicators principles on a company-wide basis.

Social Construction: Understanding Construction in a Human Context

As lean construction has evolved as a practice, efforts have been made to develop theoretical foundations for understanding it. These efforts have been informed by our understanding of lean manufacturing, a source of many of the seminal ideas for lean construction. One key insight has been the shift from the understanding of a process as the transformation of materials from inputs to outputs to the view of a process as a flow of materials through a sequence of steps or operations. Another has been the recognition that value must be considered from the customer perspective. More recently, several authors have proposed more general contexts for understanding the entire construction process. These proposals have included observing the essential role of language in the conduct of projects, recognizing the limitations of a purely economic context, and adopting a more comprehensive flow perspective. In this paper, we propose a framework for situating the construction process in the world of human concerns.

We show that consideration of the human being as actor within a world of concerns provides a necessary context and foundational explanation for all subsequent discussions of process, flow, value, and commitment. We also suggest a new perspective for understanding and addressing the issue of risk.

Construction Supply Chain Maturity Model: Conceptual Framework

Construction supply chain management has been researched and discussed in various academic and industry segments for a few years now. Members of FIATECH are discussing and defining the processes, standards, and schemas around construction supply chain management. There is a growing realization among the members of the AEC community of the need to remove inefficiencies in the construction supply chain and improve operational excellence, but the steps to achieve them is not clear.

In this paper, the authors will present a conceptual framework of construction supply chain maturity model (CSCMM) to address the above issues, drawing on similar research done in manufacturing supply chains and software processes. The objective of the framework will be to provide a roadmap for members to realizing operational excellence so that collectively the construction project can realize the benefits of improved performance. This paper will explore the maturity model and its benefits to performance of both firm level and construction project level performance.

Contingency Management in Construction Projects: A Survey of Spanish Contractors

The delivery of any construction project faces risk and uncertainty. Contingencies cover residual risks and absorb both variability and uncertainty. The management of contingencies plays a key role in improving risk management and project performance. Background literature reports that construction companies usually set time and cost contingencies with the goal of protecting project objectives. It also states that construction companies identify and manage opportunities in order to enhance project performance. Likewise, despite the fact some companies maintain formal procedures to manage risk, contingencies are often defined in a subjective and non-systematic manner. Background literature presents several methods to improve the management of contingencies; however, it seems that many practitioners either do not know them or do not use them. Therefore, a sound characterization of how construction companies currently manage contingencies is required.

The major goal of this research is to explore how construction companies currently manage contingencies. In order to do that, types of contingencies, major success factors, drivers, benefits and barriers faced by construction companies managing contingencies on construction projects are characterized. A survey (questionnaire) developed in two Spanish construction companies is described and its results are analyzed. This research aims to shape contingencies as a driver of process improvement in construction. Conclusions will help practitioners to deal with risk and uncertainty in construction projects.

An Experiment With Leading Indicators for Safety

Safety and organization of a construction site were improved with the application of safety leading indicators and a 5S assessment tool on a project managed using Lean principles. This paper is a report on a project built for a medical device company that manufactures stents and catheters. The $14,000,000 project included two high-tech ISO 8 clean rooms and associated laboratories. Safety related data collected on safety walks on a daily basis was organized for each specialty contractor and normalized for worker hours. This data helped the project focus on areas and trade partners of greatest exposure. The result on the second phase of the project showed significant improvements. The implementation of the 5-S assessment rated the site organization from zero to five for each contractor by a variety of key stakeholders. The results of the 5-S program clustered at the low end at the beginning of the project and significantly improved over time and reached almost 5 as the project approached completion.

The paper will reflect on related conceptual foundations and propose follow up investigations aimed at exploring leading indicators and other assessment tools related to safety and quality of work.

Understanding Construction Supply Chains: An Alternative Interpretation

Much research work has assessed that construction is ineffective and many problems can be observed. Analysis of these problems has shown that a major part of them are supply chain problems, originating at the interfaces of different parties or functions. There have been several kinds of initiatives aiming at improvement and renewal of construction supply chains, but only few have a track record of consequent and significant successes.

Here construction supply chains are approached from an alternative theoretical viewpoint, namely that of the language/action perspective. In this approach, organizations are seen as networks of commitments. Two avenues have been pinpointed for practical application of this approach. First, the process of requesting, creating and monitoring commitments can be facilitated by heuristic models and computer systems, when suitably designed. Secondly, people can learn to communicate for action by developing new sensibility towards the ways their language acts participate in networks of human commitments, and improving their skills in understanding requests, and making commitments. By closer study, existing empirical observations support the idea that a large share of construction supply chain problems are caused by poor articulation and activation of commitments.

But would this new approach also facilitate the implementation of a new supply chain management that has proved to be so difficult in practice? In this regard, two initiatives are reviewed. The Dutch initiative to create a framework for communication in large civil engineering projects is first presented and initial experiences from its implementation are discussed. Then, Last Planner implementations are analyzed. By drawing on the concept of small wins, it is concluded that these implementations act as a stimulus for wider changes towards an environment of firm commitments and high trust.

The paper ends with a review on research tasks ahead.

Parade Game: Impact of Work Flow Variability on Succeeding Trade Performance

The Parade Game illustrates what impact work-flow variability has on the performance of construction trades and their successors. The game consists of simulating a construction process in which resources produced by one trade are prerequisite to starting work by the next trade. Production-level detail, describing resources being passed from one trade to the next, illustrates that throughput will be reduced, project completion delayed, and waste increased by variations in flow. The game shows that it is possible to reduce waste and shorten project duration by improving the reliability of work flow between trades. Basic production management concepts are thus applied to construction management. They highlight one of the shortcomings of using CPM for field-level planning, which is that CPM does not explicitly represent reliability.

The Parade Game can be played in a classroom setting either by hand or using a computer. Computer simulation enables students to experiment with numerous alternatives in order to sharpen their intuition regarding variability, process throughput, buffers, productivity, and crew sizing. Managers interested in schedule compression will benefit from understanding work-flow variability’s impact on succeeding trade performance.

A Cognitive Systems Engineering Perspective of Construction Safety

In recent IGLC Conferences some papers have taken a cognitive systems engineering perspective of construction safety. The assumption underlying those papers has been that traditional safety management tools have failed to recognize that it is unavoidable to work close to edge where control is lost and that new mechanisms are necessary to increase the ability of workers to work safely under such circumstances. Based on data collected in five construction sites in which the authors have implemented a Safety Planning and Control model, this paper sets a preliminary discussion on the applicability of some cognitive systems engineering concepts to construction safety.

Due to the nature of the data available, the discussion is structured in four topics: identification of pressures and performance migrations towards unsafe zones of work; pre-task safety planning as a mechanism to develop judgment in workers; visibility of the boundaries of safe performance; incident analysis from the cognitive perspective. A set of opportunities for future research is outlined, such as the development of mechanisms to both identify and monitor pressures and the development of structured protocols to carry out investigations from a cognitive perspective.

Aligning the Lean Organization: A Contractual Approach

Maximizing value and minimizing waste at the project level is difficult when the contractual structure inhibits coordination, stifles cooperation and innovation, and rewards individual contractors for both reserving good ideas, and optimizing their performance at the expense of others.

This paper describes an innovative contractual structure that aligns the interests of all contractors with the objectives of the lean delivery system. The approach, requirements for implementation, and results obtained will be described and a brief reflection on theory offered.

Performance Improvement Programs and Lean Construction

The paper examines the relationship between Lean Construction and Performance Improvement programs in construction organizations. The authors argue that the structure and focus of existing performance improvement programs are a barrier to Lean Construction’s entry into the organization.

The paper first analyzes the characteristics of successful performance improvement programs, and develops a model that identifies three critical elements: 1) Time Spent on Improvement, 2) Improvement Skills and Mechanisms, and 3) Improvement Perspective and Goals.

The authors identify different ways to “structure” the improvement program: outcome focused (such as Critical Success Factors) and process focused (such as Lean Construction). The paper discusses the implications of the different “perspectives” and argues that they lead to different improvement approaches each reflecting different paradigms for the nature of the change. The authors propose that “result-focused” improvement programs may be a barrier to the adoption of Lean Construction.

Reflections on Money and Lean Construction

Money is a particularly tricky resource to manage because it comes with its own set of rules. Value is created by the application of cost concerns to choices in design. Likewise cash flow considerations during construction may lead to adjusting design to minimize risk of schedule overrun. Here again the role of money is to help clarify value for the client. In some cases the speed of the project may be limited by the rate of cash flow and while managing to assure no overrun how ever small is simplified by reliable work flow, some additional time should be added to the schedule to account for variations in cash flow. By contrast, if a precise and rapid completion date established early in the project is important to an owner, steps must be taken to insure the project is not sensitive to disruptions which might cause the project to be late. In this case, a buffer of additional money is prudent. In either case, the problem of matching cash flow to construction demands is eased by reliable workflow.

Managing Promises With the Last Planner System: Closing in on Uninterrupted Flow

The Last Planner System has been in use for about 10 years. During that time the basic structure of the system is unchanged. However, the practices for using the LPS have continued to evolve. In our paper Linguistic Action: Contributing to the Theory of Lean Construction we showed how the structure and usual practices of the LPS creates the situation for making promises reliably. In a following paper Leadership and Project Management: Time for a Change from Fayol to Flores we introduced our understanding of management and the actions needed to change to support operating a project as a network of commitments.

In this paper we build on the language-action perspective to propose a key set of distinctions and set of practices for delivering promises on a reliable basis; we call that managing promises. The combination of promising reliably and managing promises creates a basis for designing production systems that are robust to the remaining breakdowns in the project setting bringing us closer to the lean thinking ideal of uninterrupted flow.

What Kind of Production is Construction?

Applicability of lean principles to construction might seem to require that construction’s differentiating characteristics be softened or explained away. This is the strategy employed by those who advocate making construction more like the manufacturing from which lean thinking originated. Following that line of thought, successive waves of implementation would leave ever smaller remainders that are not yet reduced to manufacturing, and consequently not yet capable of being made lean. This approach offers tremendous opportunity for reducing the time and cost of constructed facilities. However, for our part, we are interested in that remainder, in understanding its peculiar characteristics, and in learning how to make it lean.

Our interest is founded on the belief that construction is a fundamentally different kind of production; i.e., that there is an irreducible remainder. We also suspect that learning how to make construction lean will help show the way to the manufacturing of the future. Manufacturing is becoming more like construction. Far from being the most backward, in our view, construction can be among the leading edge industries in lean thinking. Adopting a single-minded strategy of transforming construction into manufacturing would be precisely the wrong thing to do.

This paper explains the need to develop lean thinking for dynamic construction and lays the groundwork for a subsequent paper “Implementing Lean Construction”, in which these strategies are further developed.

An Optimised Project Requires Optimised Incentives

Lean projects seek to optimise the project rather than its parts and to maximize value to the customer. Traditional economic incentives can get in the way of that behaviour. To better align the behaviour of project participants with a Lean project delivery model, compensation structures at both the company-to-individual level and inter- company contract level need to better address both the economic and non-economic motives that impact project performance.

Hypothesis: Social science research increasingly shows that non-economic human motives play a key role in job performance, and that they interact in complicated ways with economic incentives. We have identified certain contract incentive principles that we believe should promote non-economic motives. We believe that because Lean projects depend greatly on the non-economic motives of participants, contract incentives that foster such non-economic motives are important for success.

By reviewing and extrapolating from relevant literature, this paper will explore certain key non-economic human motives and their impact on project performance, how these non-economic motives interact with economic incentives, and strategies for structuring effective incentives. The conclusion will suggest areas for further research.

An Update on Last Planner

The Last Planner system of production control has now been in use for a number of years. Its inventors provide an update consisting of a description of innovations and changes, thoughts on theoretical foundations, proposals regarding work structuring, phase scheduling and reliable promising, and recommendations for further development. Special emphasis is placed on the relationship between scheduling and production control, and also on the technique of phase scheduling to specify the handoffs that are the control foci for Last Planner.

Reaching a Lean Transformation Tipping Point

By Klaus Lemke

This is the time of year when I start to get cabin fever. I love winters in Minnesota — even the process of bundling up to go for a walk in below-zero temperatures provides a certain satisfaction for me. Yet, there is nothing like a couple warm sunny days to get me thinking about spring. Even though it’s still a couple months away, I start to anticipate the moment when my local lake transforms from a solid to a liquid again — ICE OUT!

Ice out happens very quickly, and a lake will go from being entirely covered with ice to entirely clear often in a single day. However, this “instant transformation” is actually the culmination of a much slower process that happens below the surface. Since water is most dense (heaviest) at 39°F, lighter, colder water in the form of ice floats at the top. As the water in a lake heats up in the spring, water that warms above freezing sinks to the bottom of the lake, leaving the ice at the top. A lake undergoes a lot of warming while the ice at the surface remains apparently intact. Then, as the water continues to warm, a tipping point is reached and the remaining ice warms until it too becomes denser and sinks to the bottom of the lake. The sudden change is actually the result of a steady, ongoing process that’s mostly unseen from the surface.

A similar tipping point happens as an organization or project undergoes a lean transformation. From the outside, the switch can seem to be effortless and happen very quickly. A culture of complacency, resentment and being stuck in old habits can be replaced overnight with a mood of openness, ambition and possibility. Yet, those on the inside know that the sudden change is the result of a gradual warming that’s been happening just below the surface.

When lean practices effortlessly take root and begin to impact the actual work at hand, it’s likely to be the culmination of deeper changes. In advance of this kind of tipping point, we see leaders learning new ways to interact with their teams, and create a culture of support, and psychological safety – where it’s safe to speak up about problems and concerns, and a team culture of swarming to resolve issues quickly and collaboratively. Animosity and defensiveness are replaced by a sense of belonging and trust in your teammates. Although it takes some time, this shift below the surface sets the stage for a sudden new effectiveness in the team.

So, what are the ways you’re warming the waters, even as the ice at the surface appears to be unaffected? Have you been successful in creating an environment that’s ripe for change? Is your organization approaching a tipping point?

I’d love to hear your thoughts and experience with creating an environment and culture that’s ready for rapid change. Some of my thoughts for bringing lean thinking to the world of projects are in the book, Better Building: Lean Practice for the Project-Driven Organization. Let me know what you think!

Building High-Performing Teams

By Jason Klous

A project is a project. Traditionally, Midion has focused its efforts on helping construction and design projects get better. We have worked with some of the largest owners in the world to build new programs for delivering critical infrastructure to support their business operations and growth while developing their people. We have been very successful in helping teams in that space over the last 20 years.

Recently, we were asked to help an owner build a high-performing team to tackle a critical project in the pharmaceutical industry. This project had nothing to do with construction. The client had accepted a request to produce a critical COVID related drug and to begin producing it in a time frame that some in the organization thought was unachievable. There was a history of underperforming inside the company that was influencing the organization’s attitude toward the project. There was no time to be stuck in resignation — this was a critical project for the organization and the global effort to combat the pandemic.

Our approach to building a high-performing project team applies, in principle, to any project team. We focus on building the capacity to coordinate action through the management of promises while quickly building trust in the team. In a high performing team, the members make clear requests of each other and manage their promises as a serious responsibility. They are aware that all the technology in the world cannot overcome a team that does not deliver on their promises to each other and their customers. When we take care of our commitments to each other, we take care of not just the commitment but also the relationship. A high-performing team demonstrates care in everything they do.

On our recent pharmaceutical project, we brought together a team of people who constituted the leadership team for the project. We used our Essential Conversations for Project Success workshops to teach the team members how to make clear requests, secure and manage reliable promises, cultivate productive moods, and build and repair trust. As they practiced this new way of being, they were also learning how to take care of each other, the larger organization, and their customers. As part of our workshops and coaching, we produced a team that could share frank and timely assessments on what change was needed to improve the team’s coordination and move quickly toward their shared goal of producing a new drug.

Projects move quickly. Unlike a sustainable manufacturing environment, we are always moving toward an end date. On a project, we do things once that we will never do again on the project. We are always moving, and deadlines, and the consequences for missing those deadlines, are always present. To be successful in the project environment, we must be skilled at having conversations that produce action, make and secure reliable promises, and we must learn to build and rebuild trust as part of working together. At the center, we need to demonstrate care in everything we do. Teams that can do these things well produce world-class results, develop amazing people, and open up new possibilities for action.

Beyond Partnering: Toward a New Approach to Project Management

Partnering is a programmatic Band-Aid on the current construction management system. Claims caused by fundamental weaknesses in this system gave rise to partnering. These weaknesses are particularly apparent on today’s complex uncertain and quick projects.Partnering exposes and partially fills a gap in current practice but has had little impact on underlying mental models, the management of production or commercial contracting. Moving beyond partnering means challenging and revising current thinking and practice.

This paper proposes that the construction process must be reconceived from the purchase of a product to a prototyping process. Changing the underlying mental model makes possible new approaches to managing production from concept through completion. In turn these approaches will suggest new ways to contract. Disputes will not vanish as they will remain an inevitable consequence of innovation but the frequency of commercial conflicts may be reduced.

The paper argues that partnering is an attempt to install important aspects of the prototyping model into the current product purchase model. Examples drawn from practice show the limits of current practices. They suggest a shift away from the primary focus on disputes arising in commercial contracting to the management of a concurrent design and construction process. Early examples of these trends are discussed and the workshop responses from industry representatives are reported. The paper closes with suggestions for future trends and a suggestion that Partnering be viewed as one of many programmatic efforts working to reform construction management.

A Network of Commitments is Not Enough

By Jason Klous

What is the difference between a promise and a commitment? According to the Oxford dictionary, the definition of a promise is a declaration or assurance that one will, or not, make a particular thing happen. In the domain of Language Action, a promise is one of the speech acts.

A commitment is being dedicated to a cause — such as fulfilling a promise. As one of the commissive speech acts as defined by JL Austin and John Searle, a promise leads to someone making a commitment toward action or bringing forth some new possibility.

Promises become fulfilled because of the action of a commitment.

One of the foundations of Lean in construction is the theory that projects are based on a network of commitments. Unfortunately, by only focusing, measuring and documenting commitments we miss the larger, highly complex, conversations in the background. In order to have a more complete picture of the complexity of the project environment, and the critical coordination elements that are missing, we should view projects as a network of conversations.

When we think of projects as a network of commitments, we are committing to only pay attention to the commitments that have been made. Indeed, the whole Last Planner System is built around securing, documenting and measuring the commitments that have been made. From the sticky notes in pull sessions to the measuring of PPC and variances in the daily huddle, the focus is on the commitments. In contrast, when we see a project as a series of conversations, we begin to observe the missing requests, declarations, and promises that are not leading to a commitment to bring about some future action. In order to attune ourselves to these conversations, we need to become different listeners not listening for information but rather what are the concerns in the background of conversations that are not leading to explicit commitments to take action. If we are observers of these missing coordination elements, we also then need to develop the capability to intervene in the conversations that are not producing action when needed.

The focus on only commitments may also be hiding a series of incomplete or missing conversations in the background of the project. In the Last Planner System, we measure our reliability in delivering on our promises but how are we measuring the quality of the conversations — missing promises, misunderstood requests, missing conditions of satisfaction? How do we build the capability to see what commitments are not being made as a result of missing conversations?

We will explore further in future posts.

Study Action Teams: Opening Minds for Organizational Change

What’s the Key to Organizational Change?

Producing cultural change in organizations has long been the holy grail of their leaders and the management consultants who work with them. Many approaches have been tried ranging from data-driven analyses of competitors and markets to psychological counseling about unfreezing and refreezing the company. Implementations of newly-developed strategies often falter and fizzle out. Planners routinely fail to take into account the strength of old mind-sets and old habits. We reluctantly realize that there is more to change than just announcing it. What can be done to produce the genuine changes in both attitude and habits that are the necessary elements of transformation?

The Oops Game: How Much Planning is Enough?

The future is unknown and unknowable. In the face of this reality, planning tries to assure an outcome certain. The “Oops Simulation” (Oops) models the dilemma experienced by every planner: “Should I spend more (time, money, resources) to improve my plan or go forward with what I have and more likely suffer an “Oops”? This problem is the sort Civil Engineers face when trying to decide how many soil samples to collect to assure the foundation design will be sufficient and most economical. This sort of problem is faced at every level in project planning: “How much effort is it worth to assure weekly work plan is 100% planning reliable? At what level of precision — week, day, hour, minute?” It is unlikely that anyone on the project could answer such a question because there are so many possible immediate and longer-term interactions with unknown consequences. This simple 9-card simulation can be used in research and teaching to study the cost and benefits of planning under uncertainty both in “economic” and human decision making terms.

At the extreme, there are two strategies in Oops Game: 1) No planning, the “Guts Ball” approach where the cost of planning is lowest and risk of an “Oops” is highest; and 2) Risk averse where the investment is made in planning until there is no risk of an “Oops.” In a third and more realistic approach, “Judgment” the decision to plan rests on an analysis the risks and likely outcomes in the situation at hand. The paper explains the simulation and its application in the classroom and as a platform for research into planning effectiveness, decision-making, and complexity.

Phase Planning Today

Since the publication of White Paper #7 “Phase Scheduling” (Ballard 2000), work on many projects has been planned with this technique by teams of varying configuration. Many teams have adapted their own approach to developing a “phase schedule”, in some cases called a “reverse phase schedule” or a “pull phase schedule”. During these planning sessions, ideas have been put in practice that improve on the original scheme and increase the benefits of producing a phase schedule. Perhaps the most significant being the conversations that the teams pursue during the exercise.

This paper will briefly describe the authors’ current approach to and practices for preparing phase schedules and how this has become, in actuality, phase planning. It will then describe how phase planning produces the project schedule as traditionally understood, and more importantly designs the network of commitments necessary to deliver each project milestone, and how understanding and using the network of commitments improves project performance.

Leveraging Software for Learning-in-Action Using Commitment-Based Planning